Researchers Seek Warning System for Destructive Waves On Great Lakes

Contrary to popular belief, Earth’s oceans do not have a monopoly on tsunamis.

Lesser known meteotsunamis are equally destructive and move just as fast in the Great Lakes.

The Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research is examining this phenomenon this week at a University of Michigan summit on developing an early warning series for these meteotsunamis. The collaborative research center was recently formed under a five year grant from that National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The name "meteotsunamis" is short for meteorological tsunami, meaning they are weather-related events. That's different than typical tsunamis more often associated with the ocean and that are giant waves caused by large displacements of water, often because of earthquakes or submarine landslides.

"When there are very intense storms that form suddenly on the lakes, that can create a pressure difference that actually pushes down on water from the surface," said Bradley Cardinale, a University of Michigan professor and director of the institute. "And as it displaces surface water, it can create waves as large as 20 feet."

The summit includes 25 experts from the National Weather Service, NOAA, Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory and several universities in states that border the lakes.

"We are happy that we can now identify the causes at this point, but we want to make sure we can forecast it so people can be warned before one comes," said Chin Wu, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor and the summit leader.

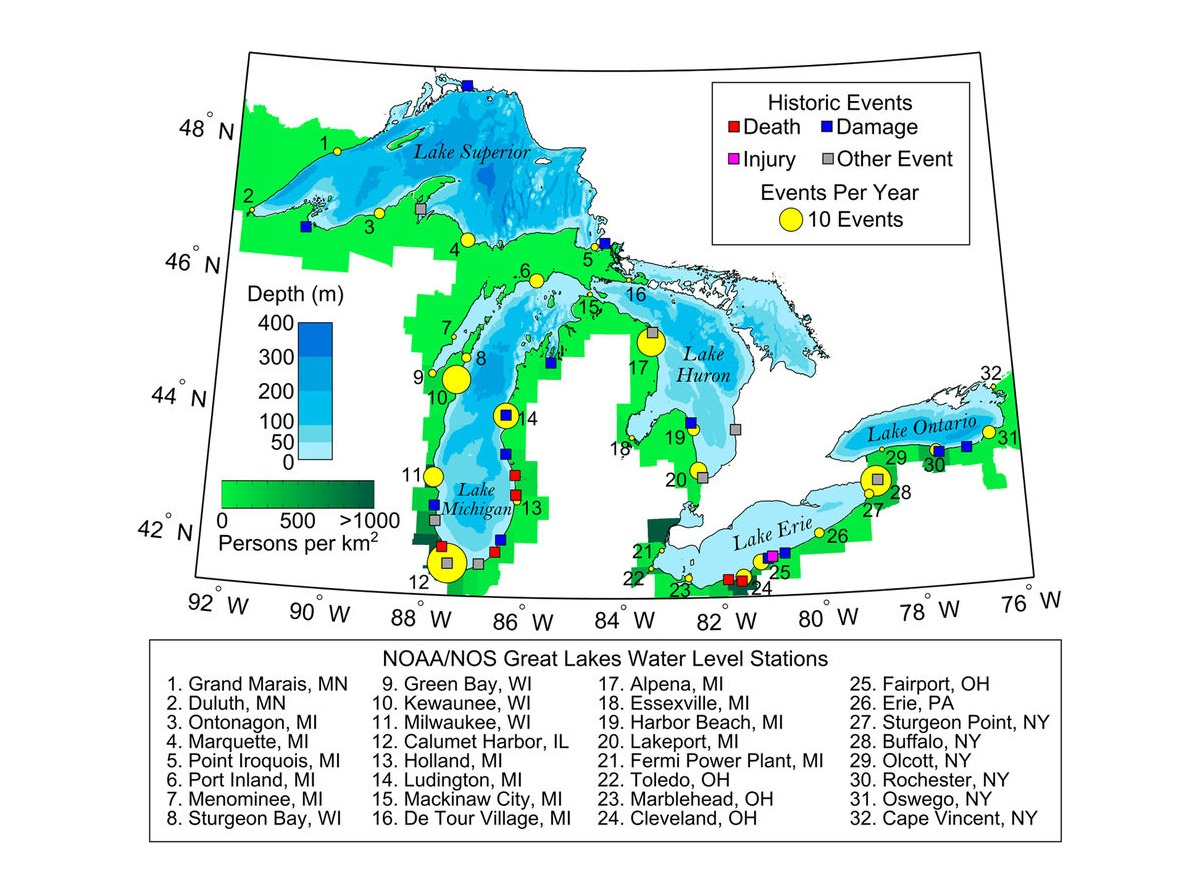

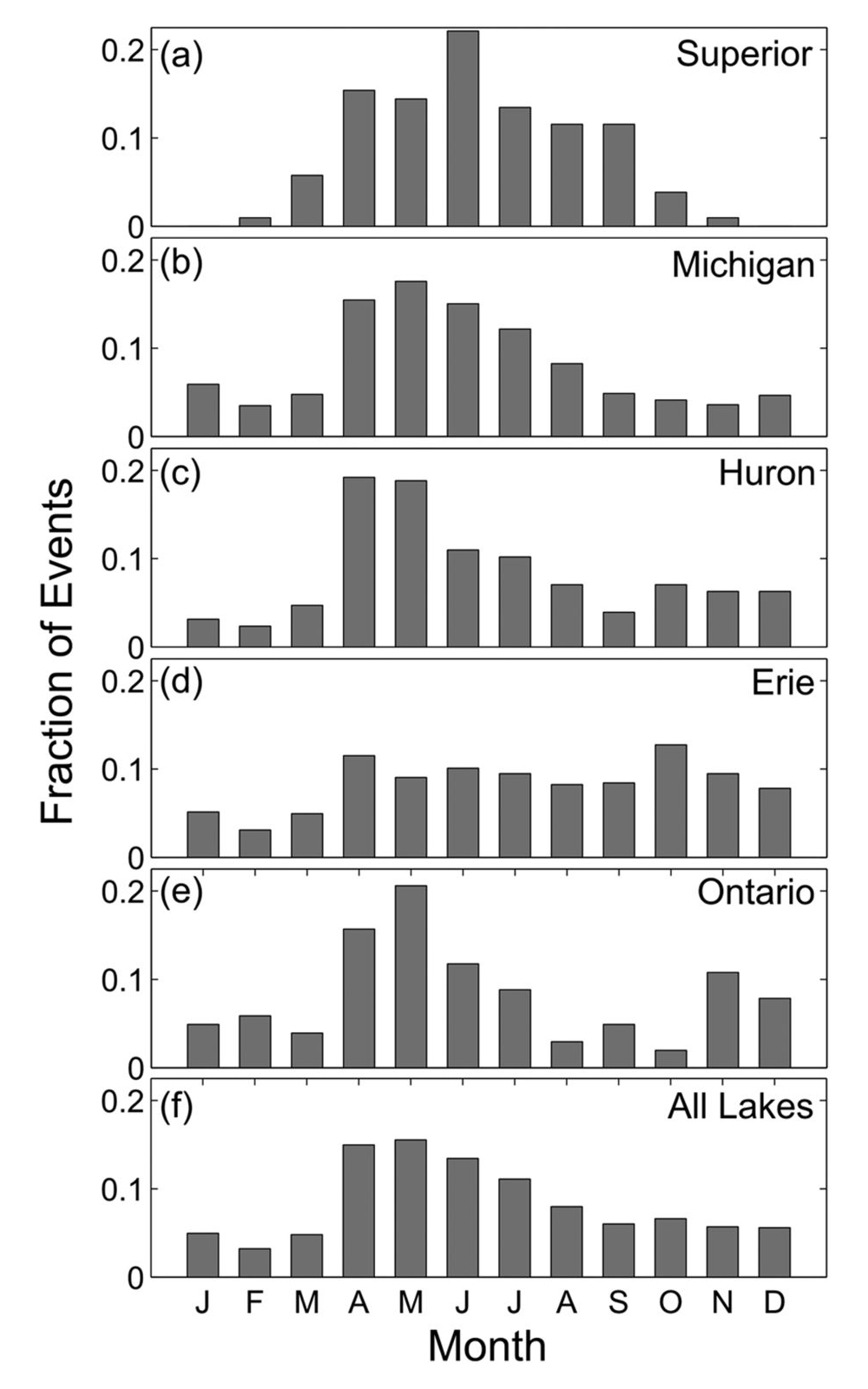

Wu found in a published study that more than 100 meteotsunamis happen every year in the Great Lakes. This is much more common than originally believed, and is predicted to climb due to climate change, the study reports. Warm surface water from global warming could create a climate conducive for stronger storms, which would cause more meteotsunamis.

The most common time for meteotsunamis is in the spring. They are most frequently sighted in the Great Lakes on Lake Michigan.

The potential growth in frequency and intensity in meteotsunami waves are among the reasons why coming up with an early warning system is important.

Often mistaken for seiches — a phenomenon where wind causes lake water to slosh back and forth, creating waves — they represent a very real threat to the region, Wu said. Cities, recreational beaches and nuclear power plants that dot the coastline are vulnerable to damage.

A warning system could save lives, property and prevent a nuclear disaster with consequences far greater than in Fukushima, Cardinale said. In the event of nuclear waste entering the Great Lakes, the contaminant would impact a resource used by millions of people and businesses.

The University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute reports that the Great Lakes provides water for 35 million people.

While most have little to no effect on the environment, researchers report several notable meteotsunamis in the Great Lakes:

- In 1929, a 20-foot wave killed 10 people in Grand Haven, Michigan.

- A 10-foot wave knocked fishermen off a pier in Chicago in 1954, killing seven.

- A particularly strong meteotsunami in 2003 capsized a tugboat in the harbor at White Lake, Michigan.

- In 2003, seven people drowned in Sawyer, Michigan, partly due to a moderate meteotsunami.

- In 2014, a meteotsunami caused water to overtop the Soo Locks in Sault Ste. Marie, disrupting shipping operations for the day.

Experts at the summit hope to start on an early warning system, and develop cooperation between relevant governmental agencies and researchers that could implement it. Experts from the Great Lakes Observing System monitor buoys and gliders that can be used in early detection.

"We're not going to come out of this meeting with a fully functionable early warning system, but it's going to be a heck of a step forward in discussions in compared to what we have right now which is nothing," Cardinale said.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on June 20, 2017 by Great Lakes Echo, which covers issues related to the environment of the Great Lakes watershed and is produced by the Knight Center for Environmental Journalism at Michigan State University.

This report is the copyright © of its original publisher. It is reproduced with permission by WisContext, a service of PBS Wisconsin and Wisconsin Public Radio.