A Tradition Of Special, And Swift, Elections In Wisconsin

Special elections are, in recent Wisconsin history, pretty mundane affairs.

When a member of Wisconsin's state Legislature or Congressional delegation leaves office before the end of their term, the governor is empowered to call a special election to fill the seat. Or, depending on the amount of time left on the incumbent's term, to not call for a special vote, leaving the seat vacant until the next regularly scheduled election.

"The governor shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies as may occur in either house of the Legislature," reads Article IV, Section 14 of the Wisconsin Constitution.

Sometimes the circumstances are tragic, when legislators die mid-term or choose to resign amid struggles with illness. More often, vacancies are the result of legislators climbing the political ladder — seeking higher office or taking appointed positions, or running for a prominent local office in their home district like mayor or county executive. Less frequently, legislators resign to take private-sector jobs, or are removed from office in the wake of a scandal. Whatever the individual circumstances of a vacancy, over the long run special elections are a fairly routine part of keeping the legislative branch running, and serve to fulfill the constitutional right of the state's citizenry to choose their own representatives.

A WisContext review of state elections records found that between 1971 and February 2018, Wisconsin has held at least 62 special elections for state Assembly seats, 40 for the state Senate and three for the U.S. House of Representatives. That's 105 special elections over nearly five decades, according to a thorough investigation of state of Wisconsin Blue Books and online records of the Legislative Reference Bureau and Wisconsin Elections Commission. In at least 33 years of the 48-year period investigated, there has been at least one special election somewhere in Wisconsin.

So, while called "special," these elections are an ongoing fact of legislative life and happen in most legislative sessions. WisContext's review of 105 special elections since 1971, as well as 45 legislative vacancies not filled through special elections over the same time period, indicates that it's pretty normal for governors to call them swiftly and without much fuss. But Gov. Scott Walker is challenging that norm with a recent decision.

Why special elections are at issue

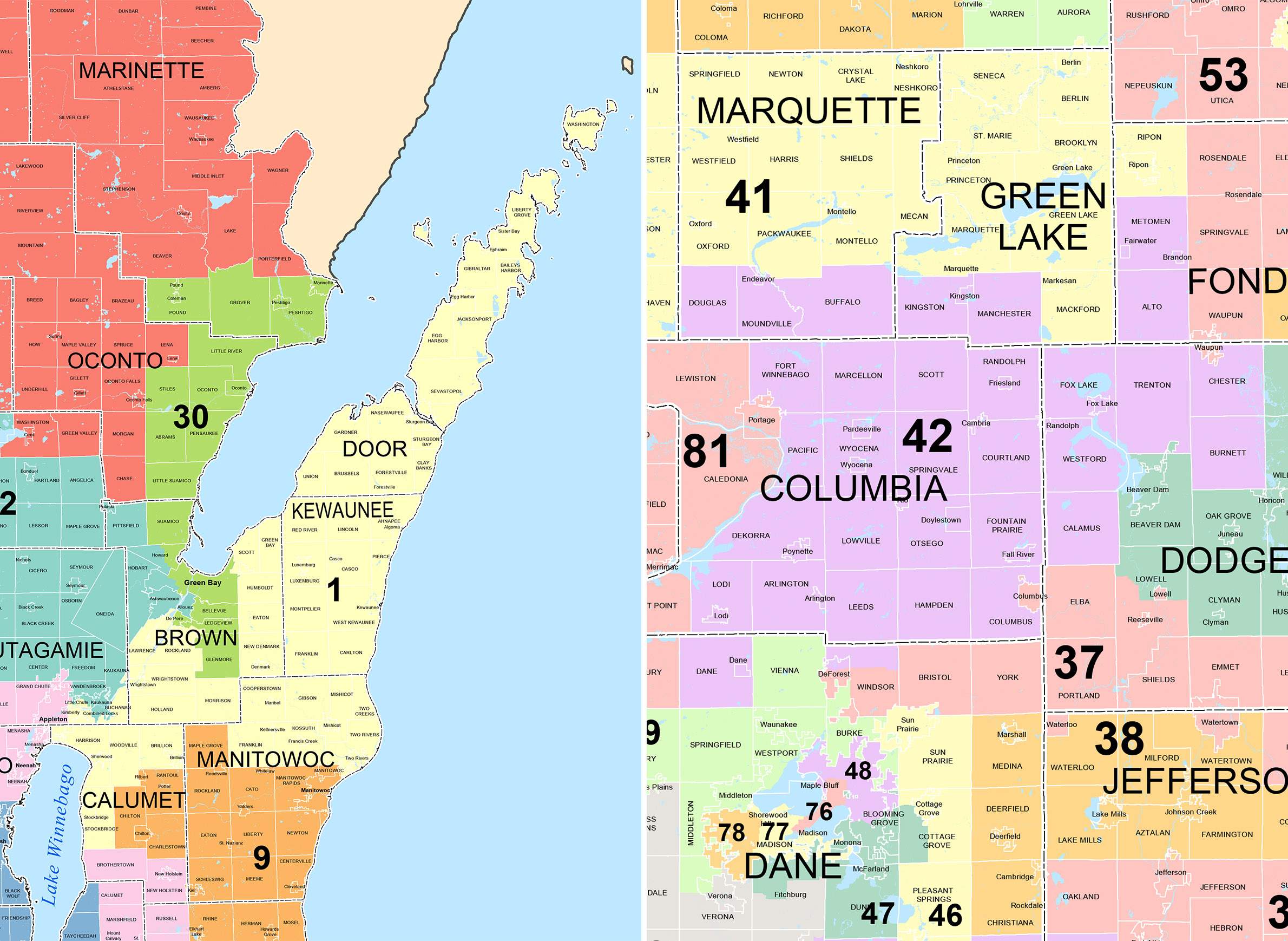

In late December 2017, the governor announced the appointment of two Republican state legislators to his administration. Frank Lasee, who represented Senate District 1, took a position at the Department of Workforce Development and Keith Ripp, who represented Assembly District 42, went to a new job at the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection— both resignations were effective on Dec. 29, 2017.

When making these hires, Walker indicated he would not call special elections for either of these districts, opting to leave them vacant until the regularly scheduled fall elections on Nov. 6, 2018. Even with those two seats vacant, Wisconsin Republicans will continue to hold comfortable majorities in both the Assembly and state Senate as each wraps up the 2018 legislative session and hold a special session.

Walker and his spokespeople say the state statutes about special elections do not require him to call special elections in this case. Walker spokesperson Tom Evenson told the Wisconsin State Journal "[t]he statute requiring a special [election] applies if a vacancy occurs in the year of the regularly scheduled election. Since Sen. Lasee and Rep. Ripp resigned in 2017, special elections are not required."

One particular phrase in the state law governing special elections (8.50) is at the heart of Walker's position: "Any vacancy in the office of state senator or representative to the assembly occurring before the 2nd Tuesday in May in the year in which a regular election is held to fill that seat shall be filled as promptly as possible by special election."

The Walker administration claims the governor's decision aligns with this requirement, because both Lasee and Ripp would have been up for reelection in 2018, but officially resigned their seats on the final weekday of 2017. If their official resignation dates were just a few days later, Walker would have been legally required to call a special election.

When a governor does call a special election, state statute requires it to be held within 62 to 77 days.

Walker intends to leave both open seats empty for about a year. In early January, the governor laid out his reasons for not calling special elections. On Jan. 18, the governor called a special legislative session involving new restrictions on public benefits like FoodShare or Medicaid. The Legislature began discussing the proposed package of legislation on Jan. 31.

Explaining his reason for not calling special elections for these two vacant seats, Walker noted if he had done so, it's unlikely that the new officeholders could be elected and sworn in before the Legislature wrapped up its sessions. With a special session, though, Walker significantly expanded the scope of what the Legislature will do whether or not these two seats are filled.

In any case, legislators work on committee-level business and interact with constituents throughout the year. The offices Lasee and Ripp previously held will still have staff around to continue some of the legislators' constituent work, but legislative staff are not the same as elected legislators.

The administration has also argued that delaying these elections saves the state money. While special elections do indeed cost money, they're part of the essential machinery of representative government — not the kind of discretionary program that's typically haggled over in terms of its price tag.

The governor's office did not provide specific figures for the cost of two special elections.

When asked for a ballpark estimate of how much it might cost to hold special elections in two districts before the November 2018 elections, Walker spokesperson Amy Hasenberg stuck to the administration's talking points in an email: "Any cost to hold a special election for these seats would be a waste of taxpayer dollars since those representatives would not be able to participate in legislative business this year. Staff is in place to ensure that constituents for both of this districts are served until new representatives are elected later this year."

State elections officials said it's difficult to generalize about the cost of special elections, which can vary based on circumstances and turnout. "We don't collect cost reports for most special elections," said Reid Magney, a spokesperson for the Wisconsin Elections Commission. "It's safe to say a special election would cost several thousand dollars to hold, but beyond that it's really hard to say without getting estimates from every county and municipal clerk in a legislative district."

Democratic leaders in the Legislature have challenged Walker's justification for not calling special elections for Lasee and Ripp's former seats. "My concern is that residents in the 1st Senate District will ultimately go approximately a year without representation," Senate Minority Leader Jennifer Shilling, D-La Crosse, told the Door County Pulse.

However, there's no escaping the partisan implications of special elections in 2018, from either the Democratic or Republican vantage point. Walker staked out his position before Patty Schachtner, a Democrat from River Falls, won a Jan. 16 special election for the state Senate's District 10 seat, which Republicans have held since 2000. But Wisconsin Republicans have been sensing vulnerability in 2018 given President Donald Trump's low approval ratings and upset Democratic wins in state legislative races in states such as Virginia.

"It's certain that any decision like this that occurs during an election year will have a strong electoral/political component to it," University of Wisconsin-Madison political scientist Kenneth Mayer said in an email.

"It seems to me that having (likely) Republican incumbents elected in April would give them more of an advantage going into November 2018. But with the result in the 10th, I don't think there's any chance that Walker would risk special elections that might produce two more surprises. Both Ripp (58.6 percent in 2016) and Lasee (61.5 percent in 2014) got lower percentages in their last elections than [Republican former District 10 state Sen. Sheila] Harsdorf (63.2 percent)."

In search of special-elections history

Gov. Walker's refusal to call special elections for the state Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 seats goes against precedent, including his own previous actions. A WisContext analysis of 105 legislative special elections in the state, from 1971 to February 2018, suggests that swiftly calling them is a well-established gubernatorial norm. In 26 of these instances, governors called a special election for a state or Congressional legislative seat before or on the same day the incumbent's resignation formally became effective. In the rest of the cases analyzed, governors waited an average of 17 days after the triggering event to call special elections.

Walker typically hasn't been one to drag his feet, calling four legislative special elections on or before the date of the incumbent's effective resignation. In 12 other cases, he waited an average of 23 days. Not that any single governor's average length indicates much — some served longer than others, and the circumstances that create legislative vacancies aren't always in a governor's control, except of course appointing state legislators to executive-branch jobs.

WisContext also examined another 45 state legislative vacancies — 13 in the Senate and 32 in the Assembly — that were not filled through special elections, based on an analysis of election dates and legislator resignations and deaths in state records. In the Senate, nearly all of these resignations or deaths came within the last few months of the sitting senator's four-year term. In most cases the senators resigning had chosen not to run for re-election and new candidates for those seats had already launched their campaigns. In some cases, the vacancies stretched on for several months, but calling a special election would not have sped up the process or would have disrupted ongoing races.

And in 32 of those 45 vacancies not filled by special elections, an Assembly or Senate seat was vacant for 100 or more days before the next regularly scheduled election to fill it. But of those, only a handful went on anywhere near as long as the vacancy Walker would allow in 2018.

Long vacancies in Wisconsin's Legislature

Of the 150 legislative seat vacancies analyzed going back to 1971— both those filled by special elections and those that were not — only seven ran for 200 or more days, and only one seems to approach a year-long gap. However, this piece of the historical record isn't entirely clear.

The Wisconsin Legislature's journals shows that Rep. John Merkt, R-Mequon, resigned the Assembly District 58 seat in December 1987, and the Wisconsin Blue Book shows the next election for that district was the general election in November 1988. However, when WisContext attempted to verify the length of this vacancy with the Legislative Reference Bureau, an analyst said Merkt announced his resignation in 1987 but didn't actually step down from his seat until some point in 1988. And indeed, digging further into the legislative journals — the same ones that indicate he resigned in 1987 — Merkt is clearly shown voting on Assembly bills well into 1988, but clearly did not run for reelection that year.

The next-longest vacancy for which the WisContext search turned up evidence came up in Assembly District 75, when Rep. Kenneth Schricker, R-Spooner, died on March 1, 1978. (According to a Wisconsin State Journal story published at the time, Schricker collapsed at St. Mary's Hospital in Madison, where he'd been seeking treatment for heart problems.) State records indicate the seat was filled in the general election on November 7, 1978, which came 251 days later and would have included a race for that district with or without a vacancy. (Technically the actual vacancy was longer, as his successor Patricia Spafford Smith, D-Shell Lake, wouldn't have been sworn in until January 1979.)

The WisContext special elections analysis does show a couple other outliers in the 1980s.

When Gerald Kleczka, D-Milwaukee, was sworn into the U.S. House of Representatives on April 10, 1984 — after being elected to Congress in a special election, after the death of former Rep. Clement Zablocki, D-Milwaukee — he vacated his seat in state Senate District 7. Lieutenant Gov. James Flynn, in the capacity of Acting Gov. during Tony Earl's administration, called a special election for the seat to take place on the day of the general election in November. This period represented a 210-day gap between the seat being vacated and the election filling it.

Additionally, after District 3 state Sen. John Norquist, D-Milwaukee, was elected mayor of Milwaukee in April 1988, formally resigning from the Legislature effective April 20, Gov. Tommy Thompson similarly called for his seat to be filled in a special election concurrent with the regularly scheduled November election. In that case, there was a 202-day gap between resignation and election.

A precedent for speedy special elections

The WisContext analysis of special elections called between 1971 and February 2018 uses information from a few sources to piece together when vacancies occurred and when governors called special elections to fill them: governors' executive orders, Wisconsin Blue Books records of election dates and results, and the Legislature's journals. Pieced together, information from these sources usually reveals when a seat became vacant, when and if the governor called a special election to fill it, and when the election was held.

As much as possible, this analysis uses the date on which a legislator's resignation became effective as the "triggering date" of the vacancy. In rare cases where this date was not available, this analysis uses the most specific available date for an event that would have triggered the vacancy, such as the date a legislator was elected to another office.

One important distinction to note is that a legislative vacancy remains open until the new officeholder is sworn in; however, this analysis uses election dates rather than swearing-in dates, because it's focused on how and when Wisconsin governors use their power to call special elections.

One reason for the time frame of this analysis was that, before the 1970s, at least some special elections were called through gubernatorial proclamations that were not executive orders. According to staff at the Legislative Reference Bureau and Wisconsin Historical Society, some of those proclamations are scattered throughout different governors' collections of papers. Due to this level of availability, WisContext set a time scale to ensure as consistent a pool of records as is available. With a time frame from 1971 to early 2018, this analysis examines a sample that spans eight governors (four Democrats and four Republicans) and nearly 50 years.

This analysis does not include special primary elections leading up to special elections, nor does it include recall elections, or special elections for non-legislative state offices like Superintendent of Public Instruction or Supreme Court Justice. The scope is specifically limited to better understand how modern Wisconsin governors have used their authority to address legislative vacancies.

Walker cuts against the norm

Sifting through the facts of special elections in Wisconsin is a complex process. However, the historical information available strongly indicates that special elections happen fairly often in Wisconsin politics, and that governors tend to call them fairly quickly when a legislative seat becomes vacant, at least since 1971.

It is beside the point to put a number on how long a "typical" legislative vacancy is. Legislators don't resign or die on a predictable schedule, though some events driving vacancies can be anticipated, like a new governor appointing sitting legislators to positions at state agencies. Some years bring more vacancies than others, while some don't have any. The exact date a special election is held for a seat is influenced by constraints of statute, logistics and political calculation.

WisContext's analysis of special elections in Wisconsin from 1971 through January 2018 did not turn up a single instance when a governor left a seat unoccupied for more than a year until the vacancies of Frank Lasee and Keith Ripp. Even vacancies in the 200-day range uncovered in this investigation began with a resignation or death in March or April, and ended with a new legislator being elected in November and sworn in by the following January.

In the case of Lasee and Ripp, both resigned at the end of December 2017, and based on Walker's decision, those seats will not be filled until January 2019. Given the timing of these resignations, both seats would have been empty through much or all of the Legislature's regular floor debate and voting schedule in 2018 even if Walker had called special elections as soon as possible. But this timing hasn't always been a barrier in the past five decades — WisContext's analysis turned up 14 instances in which legislators vacated their seats in December, including some resignations in odd-numbered years, and the governor at the time called a special election for March, April or May.

Walker's legal rationale for not calling special elections in Senate District 1 and Assembly District 42 might take a court battle to sort out — it has the makings of a classic conflict between the letter and spirit of a law. But whatever the legal and political technicalities, the record of the past several decades of state history shows that it's an unusual decision indeed.