How Ice Jams And Lingering Snowpack Contribute To Spring Flooding In Wisconsin

Spring flooding is a familiar frustration around Wisconsin — it's about as expected as a dangerous blizzard striking in winter. But a confluence of difficult conditions beginning in the summer of 2018 and building through early 2019 have led to unexpectedly big and damaging flooding across the Midwest.

Nebraska has seen some of the worst flooding of the spring so far, where record high waters left three people dead and have inundated broad swaths of farmland.

In Wisconsin, ice-jam flooding along the Fond Du Lac River forced the evacuation of some residents in the surrounding city and county of the same name. City crews worked to haul away ice and clear the river in attempts to slow the flooding. To the west in Columbia County, Spring Creek, which flows through Lodi, reached record levels as well. Community members came together to fill and distribute more that 10,000 sandbags.

"It was just something like I've never seen before," Lodi resident Sue Benson told Wisconsin Public Radio. "You see it on TV. And you say, 'Oh that's horrible. Those poor people.' And then you go about your business OK. When it happens to you, boy is it another whole story in itself."

But it wasn’t just southern Wisconsin dealing with the effects of ice jams and high rivers. National Weather Service offices issued flood warnings for rivers throughout the state. In northeastern Wisconsin, the Oconto, Fox and Wolf Rivers have been at risk of flooding caused by melting snow and exacerbated by ice jams.

Here is a look at the East River near Greenleaf, WI. A VERY quick rise in the water level due to the warmer temps, snow melt, a possible ice jam and rainfall. Conditions can change quickly! Be alert! Never drive into a flooded roadway.

— NWS Green Bay (@NWSGreenBay) March 14, 2019

Thanks to the USGS for the webcam. #wiwx pic.twitter.com/iLY5CDQW4N

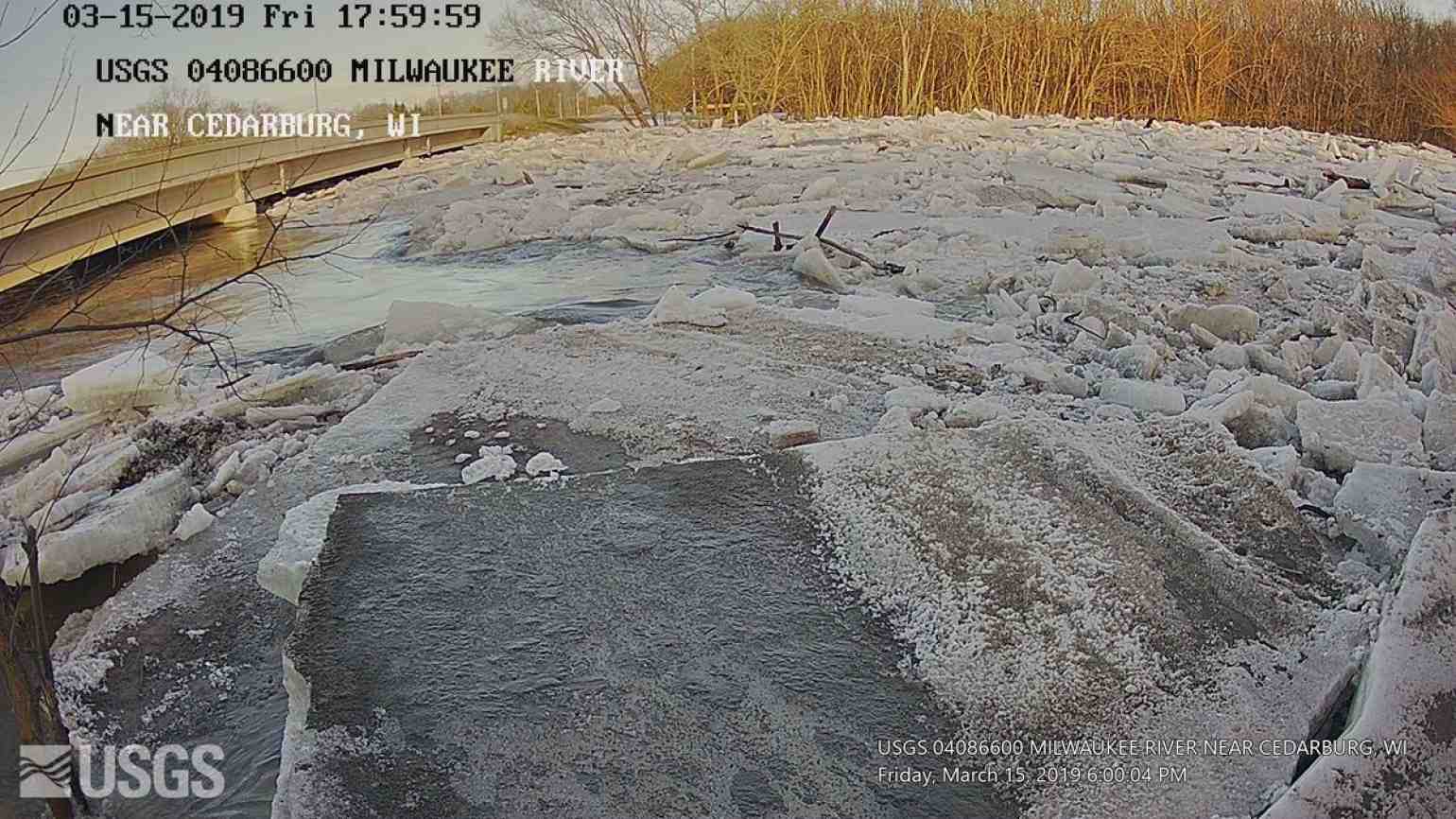

Ice jams occur on rivers when floating ice runs into an obstruction and piles up, acting like a dam. The water level rises in turn and overflows barriers in those locations, which can lead to flooding. A lot of ice jams occur around bridges. They can also occur in urban areas, at spots like backed-up storm sewers. Though this flooding is typically on a smaller scale than on rivers, it can still cause damage.

Areas along the Mississippi River have likewise faced potential major flooding, depending on the rate the snow melts and and whether the region will see any additional rainfall, Wisconsin Public Radio reported. The National Weather Service tracks water levels on the Mississippi River, and multiple Wisconsin communities are approaching or at flood stages.

The need for caution when addressing spring flooding in Wisconsin is heightened by the major floods parts of the state saw in August 2018.

Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, said the state is still working to recover from the previous summer's floods. He explained this issue on a March 7, 2019 interview on WPR's The Morning Show.

"Recovery from a large flood like what happened in Dane County and the region often takes years," Berginnis said. "It's going to take several years for folks to recover and get back to normal."

On March 15, Gov. Tony Evers declared a state of emergency for all of Wisconsin in response to the widespread flooding.

Due to the record amount of snow Wisconsin received in February, as well as the state’s elevated river levels, ice jams and generally saturated soils, the state is at an elevated risk for flooding for at least another month. That's the outlook from the National Weather Service's North Central River Forecast Center, which tracks hydrologic conditions and issues flood and other weather-related forecasts. Andrew Mangham is a hydrologist with the Center who monitors flooding conditions around the Upper Midwest.

In a March 18 interview with Wisconsin Public Television's Here & Now, Mangham remained hopeful that the spring's weather will cooperate and provide a gradual snow melt.

"We're hoping that we get a sort of 'maple syrup spring' where we get slightly warm days and cold nights that can bleed off the snowpacks slowly," he said.

The type of devastation seen in Nebraska, Iowa and Missouri is what Mangham called a "worst case scenario" in a follow-up interview with WisContext. He noted that flooding of that scale hasn't occurred in Wisconsin since 1965.

What set the stage for catastrophic flooding in Nebraska — as well as Wisconsin in 1965 — was a combination of factors, including a large snow pack, frozen ground, rapid warming followed by heavy rains, Mangham explained.

Wisconsin is currently dealing with many of these factors: due to heavy February snows, the snowpack across the northern half of state remain high, the ground in many places has yet to fully thaw, and soils are saturated due to flooding in 2018.

This is our (North Central River Forecast Center) current maps showing current flood levels and 7-day flood outlook across the upper Miss. #flood #forecast #preparedness pic.twitter.com/sqNaoydbv0

— NWS NCRFC (@NWSncrfc) March 21, 2019

The state hasn't faced the same type of destructive flooding as Nebraska because — so far — there has been no massive rainstorm to accompany the spring's warm temperatures, Mangham said.

"We sort of got lucky," he said.

But even if Wisconsin has been fortunate so far, the state Department of Military Affairs estimates spring flooding has cost local governments nearly $2 million in damages.