The Race To Watch And Listen For Bats As They Disappear

Wisconsin's bats are in trouble — at least those that hibernate in caves. An invasive fungus from Eurasia is spreading westward across North America and infecting bats during winter hibernation. In cave after cave where the fungus arrives, mass death of hibernating bats inevitably follows.

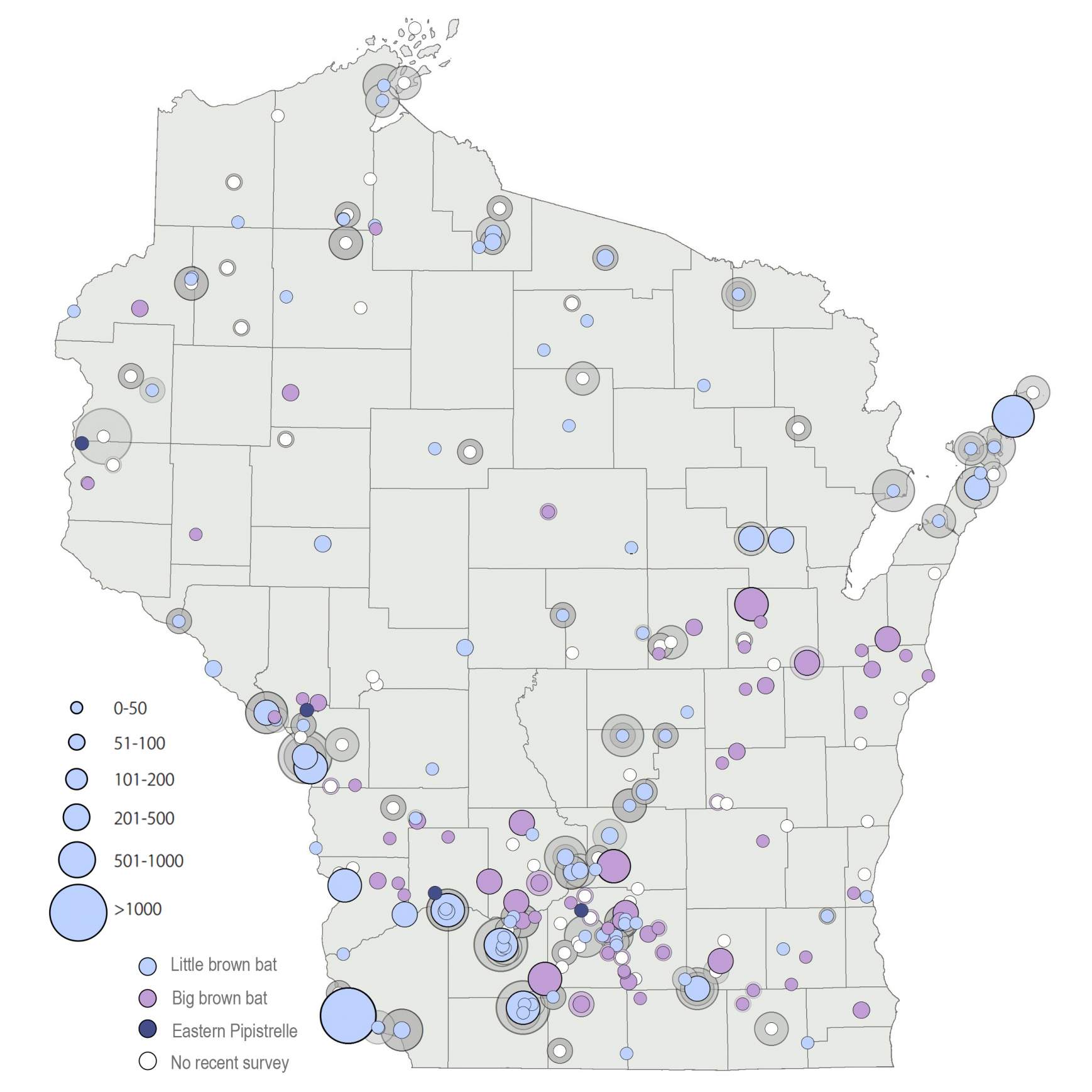

Data gathered by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the National Park Service demonstrate this crisis: Populations of three bat species have fallen precipitously throughout Wisconsin since 2014, when the ailment known as white-nose syndrome was first recorded in Grant County.

But how can all of the state's tiny, elusive nocturnal flyers be counted? That's not possible. But the downward spiral of these bats can be tracked through the work of passionate conservation professionals, specialized technology and, crucially, legions of enthusiastic volunteers.

This bat-counting infrastructure is a relatively new development in Wisconsin. It's the product of some prescient scientists who saw trouble brewing for the state's bats as white-nose syndrome began its march west from New York, where it originated more than a decade ago.

The origins of bat monitoring in Wisconsin

Years before white-nose syndrome's emergence in Wisconsin, a DNR ecologist with a love for flying mammals began assembling the resources that would prove crucial to building a bat counting network.

That ecologist, David Redell, recognized early on that white-nose syndrome’s entrance into Wisconsin was likely inevitable.

"There's basically a crisis in front of us," said Redell in an October 2010 story about the looming threat on an episode of PBS Wisconsin's In Wisconsin.

"We don't have a lot of time," he added.

Redell and his colleagues began a race against the clock to figure out how best to count Wisconsin's hibernating bats before the disease arrived. Having pre-disease population data was critical if wildlife managers were to understand white-nose syndrome's eventual impact.

So, DNR staff inventoried the state's bat hibernation sites, devised monitoring methods and leveraged growing interest in bats among the public to form the Wisconsin Bat Program. The program is now the nexus of the state’s various bat monitoring endeavors, which began in full force just in time to provide essential data prior to white-nose syndrome's arrival.

Redell died from an aggressive cancer in 2012 at the age of 42, just as the fruits of this labor were taking shape.

"We wouldn't really be thinking about bats or even talking about bats today if it weren't for David Redell," said J. Paul White, a mammal ecologist with the DNR who now oversees the bat program.

"We are standing on the shoulders of much of the work that he has done to lay the foundation for not only the Wisconsin bat monitoring program, but just to put Wisconsin in a proactive stance … when white-nose syndrome was first on the scene."

Counting hibernating bats

In many ways, Wisconsin's proactive approach resembles those in other states, all of which adhere to protocol developed by the United States Fish & Wildlife Service. In Wisconsin, the DNR began with compiling as complete a record as it could of sites in the state where bats are known to hibernate. Called hibernacula, these sites range from natural caves to mines and even buildings.

Knowing where hibernacula are on the landscape is important, not only because bats are easier to count when they're amassed in hibernating colonies, but because those places are where the cold-loving fungus that causes white-nose syndrome infects and kills bats.

After combing through cave records and historical mining databases, as well as collecting information from private landowners, the DNR counted over 60 hibernacula in the state. These sites were known to house anywhere from hundreds to many thousands of bats in any given year, with many of them hosting all four hibernating species: big brown (Eptesicus fuscus), little brown (Myotis lucifugus), northern long-eared (Myotis septentrionalis) and tri-colored, also known as the Eastern pipistrelle (Perimyotis subflavus).

Gathering population estimates of Wisconsin's four hibernating bat species was as simple as counting their numbers each winter within known hibernacula. DNR staff began systematic counts in 2013, only a year before white-nose syndrome was detected in the state for the first time.

"From there, you can get a population estimate, and then you can look at it from year to year and see what the declines are," said DNR biologist J. Paul White.

Those declines have generally been steep within the 30 hibernacula the DNR has consistently monitored since before the arrival of white-nose syndrome.

As of March 2019, little brown bat populations at those sites had fallen from around 160,000 to 40,000, or about a 73% reduction from their pre-disease numbers. Tri-colored bats dropped by 90%. Northern long-eared bats fared the worst, falling a staggering 97%. On the other hand, big brown populations were also reduced, but not as severely at 23%.

Counting bats in the summer

Surveys of hibernating bats are only one part of the Wisconsin's multi-pronged monitoring approach. The DNR also counts bats during the summer to get a better sense of their reproductive trends, and to supplement its hibernacula records with data from a wider geographic range and collected by many more individuals, including volunteers from the agency's Wisconsin Citizen-based Monitoring Network.

Summertime monitoring includes the annual "Great Wisconsin Bat Count," during which hundreds of volunteers stake out sites where hibernating bats are known to gather and roost in large numbers while rearing their young. These sites tend to be near water, so in Wisconsin they're spread across the state, as opposed to hibernacula which are concentrated mostly in its southern and western stretches.

"Bats are obviously really mobile, and so in the summer they'll move anywhere where they find particularly good roosting and foraging habitat," said Heather Kaarakka, a conservation biologist at the DNR. "And that means, at least for the little brown bat and for the big brown bat to a certain extent, that pretty much anywhere there's water in Wisconsin, they're going to be found."

"Or," she added, "at least they were found."

The summer roost counts occur twice annually: once in late spring, before bat pups are able to fly (called pre-volancy) and the other in late summer after pups have started flying (post-volancy). This pair of counts helps with understanding the bats' reproductive success each year and how it figures into population trends.

A 2012 video from the Wisconsin Citizen-based Monitoring Network details the process.

Volunteers count the bats one by one as they exit roost sites — often constructed bat boxes — around dusk. Similar to the data collected from hibernacula, the summer roost counts show significant decline at many roost sites throughout the state, though the declines vary by location and species.

The summer counts aren’t simply a source of useful data about bats' populations and reproductive success. Because they depend on hundreds of volunteers, the counts also serve as a public outreach tool by keeping bats and their plight front of mind among a wider group of concerned civilians.

Two of those volunteers are Tom and Susi Irwin, of Madison, who counted dozens of little brown and big brown bats take off from a bat box at Yellowstone Lake State Park on a steamy evening in August 2019.

The Irwins' affinity for bats grew from a place that many Wisconsinites might find relatable: They appreciate the mammals' summertime service of gobbling up millions of mosquitoes and other insects. Over the past several years, the Irwins have perceived a decline in bats — and increase in bugs — at their cabin on Loon Lake in Langlade County.

"There are so many mosquitoes on Loon Lake," said Tom Irwin. "The bats will eat thousands of them, and more power to them."

"So we just got interested in them and knew that [the DNR was] looking for people that could help monitor," said Susi Irwin. "They don't have enough staff to come out in the field and do all this."

Bats' voracious appetite for insects provides benefits well beyond outdoor comfort. They eat so many bugs that scientists estimate they provide billions of dollars in economic value to the nation's farmers and foresters, including a value of around $650 million in Wisconsin. Bats also play important ecological roles as pollinators, seed dispersers and in cave ecosystems.

The Great Wisconsin Bat Count numbers shows little brown bats on the decline across Wisconsin over the 5-year period between 2015 and 2019.

Big brown bats again appear to be hanging better than the little browns, possibly because they hibernate in more diverse sites, including buildings, where they are less likely to come into contact with disease-causing fungus.

Monitoring through sound

As the Irwins were counting the bats they could see on a summer night at a state park, the couple also brought along a device that allowed them to hear the little critters. It was more for fun than science on that particular excursion, but similar technologies provide one more important avenue for estimating bat populations in Wisconsin.

Bats' nocturnal existence has placed a particular importance on sounds for various species. To help navigate dark skies and even darker caves, Wisconsin's cave bats emit high-frequency sounds that bounce back at them after hitting obstructions like trees, buildings and cavern walls. Their brains can process that aural information to piece together their surroundings, an adaptation known as echolocation that these bats share with a few other animals like dolphins. And similar to those species, bats apply the same adaptation to locating prey and possibly communicating with one another.

The pitch of bat calls is so high, however, that humans are unable to perceive them. Luckily for Wisconsin's bat monitoring efforts, some straightforward yet specialized technologies can help overcome this hurdle.

Known broadly as "acoustic monitors" and taking various forms from handheld devices like the Irwins' to larger and more elaborate ground setups, the technologies empower scientists with the DNR and elsewhere to monitor bat populations more passively and continuously.

This ability is very useful in remote settings like the Apostle Islands on the south shore of Lake Superior. Most of the islands are a part of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, a federal park managed by the National Park Service.

Since 2015, the Park Service has deployed an array of acoustic monitors across the archipelago to listen for bats. The monitors join others at all of its Great Lakes region properties, including the St. Croix National Scenic Riverway in northwest Wisconsin.

The monitors consist of a microphone that can detect bats' high-pitched calls and a device to record whatever calls is picked up. Upon setup, the monitors can be left to passively listen for bats for days or weeks at a time until a scientist is able to return to collect the data for analysis.

Because individual bat species have unique calls that the microphones are able to distinguish these analyses can provide information both the relative number of any given species in an area. They've shown that an increasing share of the echolocation calls recorded in both parks can be attributed to non-hibernating species, which aren't affected by white-nose syndrome. Indeed, the acoustic monitors have detected a drop in calls from little brown bats in particular relative to other species.

"The decline in little brown bat activity is more significant (so far) at St. Croix than the Apostle Islands," Katy Goodwin noted in an email.

Goodwin is the bat monitoring project coordinator for the Park Service's Great Lakes Inventory & Monitoring Network.

"One possible explanation is that the bats who spend the summer at St. Croix may hibernate at different locations than the bats that spend the summer at the Apostle Islands, and potentially were using hibernacula that had higher [white-nose syndrome] rates," she continued.

Still, Goodwin stressed that this was a guess, demonstrating one of many uncertainties researchers continue to face in their struggle to understand how white-nose syndrome is affecting bats even as they collect ever more data.

And yet, the data are clear about one thing: Species like the little brown and northern long-eared bat are quickly disappearing from Wisconsin.

"The loss of little brown bats is very evident in the acoustic surveys, primarily in the north, where there's been a few active [DNR] programs in that part of the state," said DNR biologist J. Paul White.

The DNR conducts acoustic monitoring as well. The agency began deploying devices at sites across the state in the late 2000s. It also lends handheld devices to volunteers who want to conduct counts while driving along roads or paddling in lakes and rivers.

"Historically, all they would get [during acoustic surveys] were little brown bats," White said. "Now, they could go out and do an hour survey and very possibly get nothing."

Signs of survival?

Wintertime hibernacula surveys have hinted at potential resilience to the disease on the part of some individual bat colonies, with very small numbers of affected species continuing to persist within infected hibernacula.

"There seems to be some sort of a stabilization," said J. Paul White, though he added that the DNR is still teasing out whether remaining individuals are newcomers or if there are some individuals surviving year to year.

"We do definitely have some information to suggest that there is a level of survivorship that is happening year to year," he said. "But to what extent? We're still trying to understand that."