Bringing Native Languages Back From The Vanishing Point

Language shapes how people view the world, build ideas and communicate with others people — it's an integral part of community culture and personal identity. But for many Native American nations, their ancestral languages are on the verge of disappearing. Over many generations, numerous Native American languages were nearly all but wiped out after the European settlement of North America. However, linguists are working with Native communities to help revitalize these traditions.

The decline and death of languages is not a new concept, noted University of Wisconsin-Madison linguistics professor Monica Macaulay. She discussed the challenges faced by Native American languages and efforts to revive them in an Aug. 26, 2015 lecture at Wednesday Nite @ the Lab on the UW-Madison campus, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television's University Place.

Macaulay explained that there are currently some 7,000 languages spoken around the world, but anywhere between 50 to 90 percent of them are expected to disappear by the end of the 21st century. This loss is due to changes in what she describes as the "ecology of languages," including factors such as the rise of more widely spoken languages and ongoing demographic shifts. When it comes to a decline in the number of people speaking Native American languages, Macaulay detailed many more factors that came into play.

In Wisconsin, there are 11 federally recognized American Indian tribes. After treaties were established in the 19th century and continuing well into the 20th, native children were taken from their homes across the country and forced to attend "residential" schools. At these schools, the children were forced to speak English and punished for speaking their own languages.

While the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 mandated that these boarding schools close, many remained opened well into the latter half of the 20th century. Macaulay explained that this practice had a major impact in the decline of Native American languages since it only takes one generation to drastically change speaking patterns in a community.

"If you think about even a language like English, if you break the chain of speaking one generation, it's gone, you know, it's gone," she said.

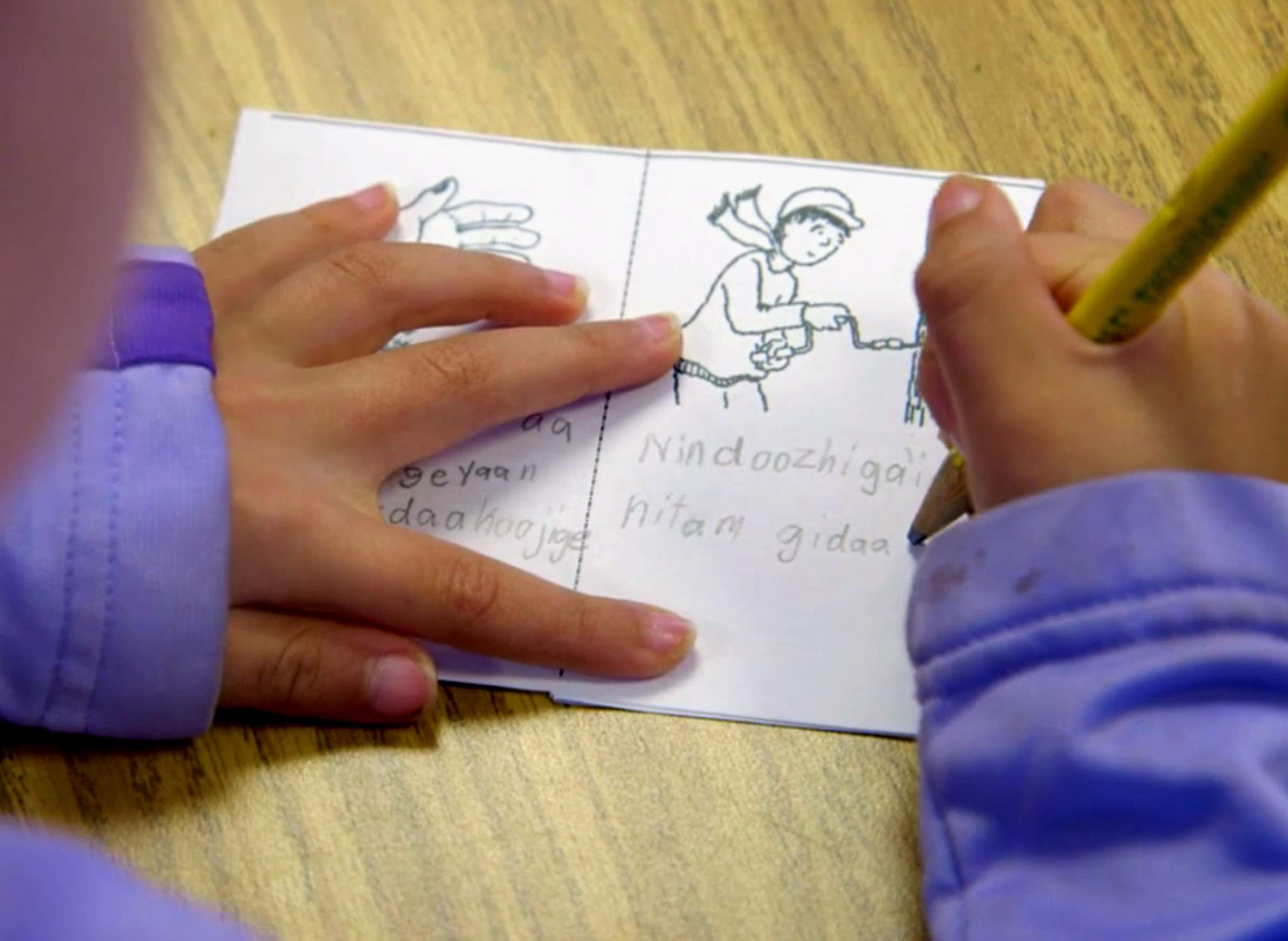

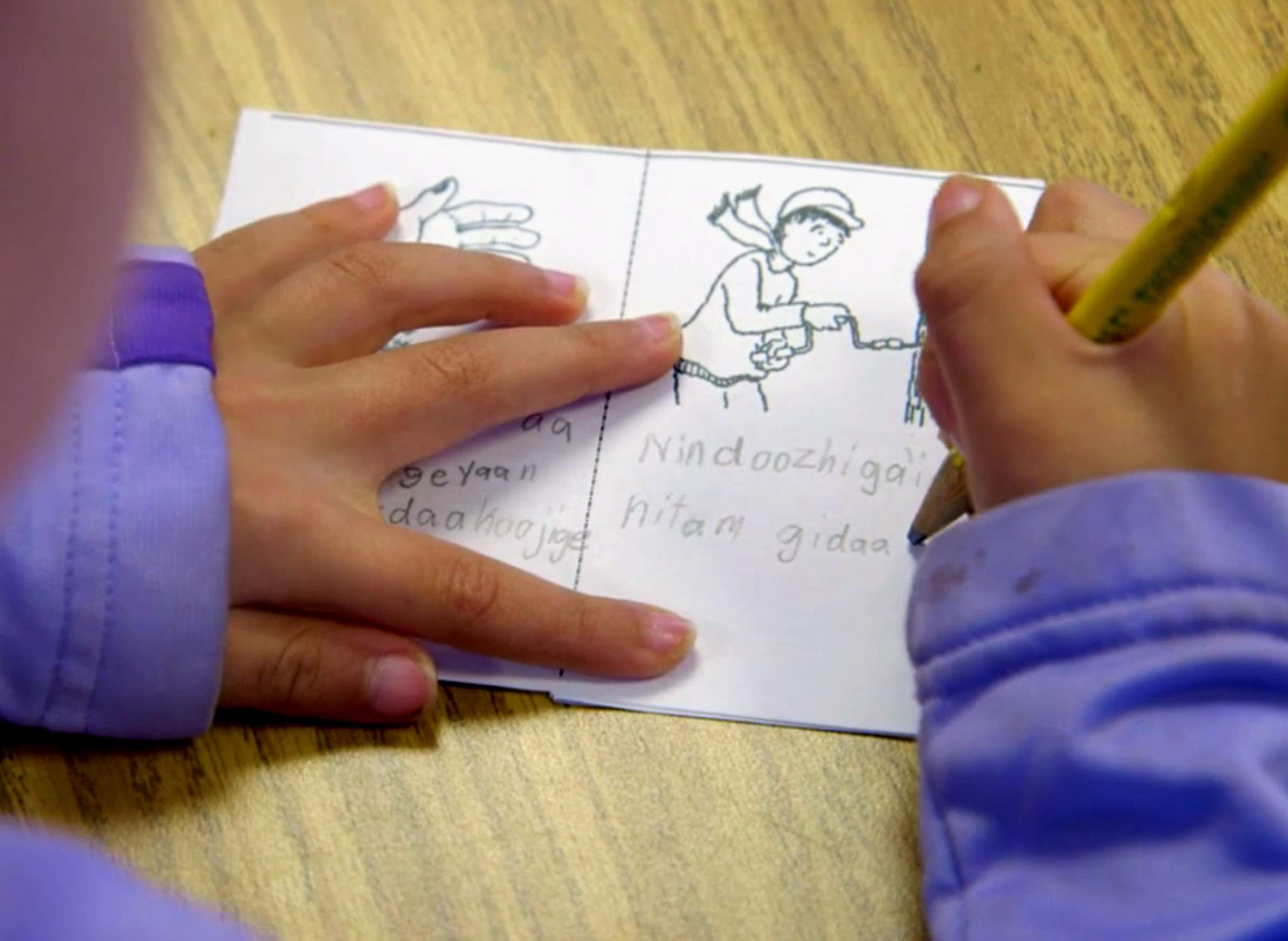

But in Wisconsin and elsewhere, emerging efforts like apprenticeship programs and new immersion schools are teaching a new generation of native language speakers. The Waadookodaading Ojibwe Language Institute in Hayward, Wisconsin, a charter school operated by the Lac Coutre Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, is a leader in Ojibwe language revitalization. At this school, all core classes are taught in the Ojibwe language.

Waadookodaading means "a place where people help each other." The school relies on help from community members and beyond to craft curriculums and even write a dictionary with new Ojibwe words used for teaching, said UW-Madison linguistics professor Rand Valentine, who also spoke at the August 2015 presentation.

"When you develop a curriculum for education and you have to pass all the requirements of the state of Wisconsin, you have to teach certain subjects," Valentine said. "Many of these subjects do not have vocabulary in the traditional language. So you have to come up with a complete curriculum. You have to invent many, many words in your language to deal with that curriculum."

The Waadookodaading school has seen great success. Its executive director, Brooke Ammann, told WPR that by the end of kindergarten, most students know two alphabets and writing systems: English and Ojibwe.

Waadookodaading isn't the only school in Wisconsin working to revitalize Native American languages. The Indian Community School in Milwaukee provides education for Native American students from pre-K through eighth grade. The biggest difference between this school and Waadookodaading is the former is a multi-tribal facility, reported WPR.

The Indian Community School has students and staff from more than a dozen tribes, and offers instruction in the Oneida, Menominee and Ojibwe languages.

Jason Dropik, the interim head of the Milwaukee-based school, emphasized the importance of children learning native languages to better connect with their cultures.

"And a lot of the cultural beliefs and different ways of being and traditions and ceremonies that are held within Native communities, they can't be held without the language," Dropik told WPR. "Keeping that language going — especially as important as language is to a person's state of being and a way of helping them navigate the world around them — is really important to us."

Key facts

- About 7,000 languages are spoken around the world in the early 21st century. Linguists estimate that between 50 to 90 percent of them will be lost by the end of the century. This expected decline is due to several factors, including demographic and economic changes around the world. Adoption of more widely spoken competitors, such as English, Spanish and Mandarin, have hastened the disappearance of rare dialects.

- For much of the late 19th and 20th centuries, many Native American children were taken to boarding schools where they were forcibly immersed in European-American culture and taught to speak English. These children were often punished for speaking their native languages and had all sense of their indigenous culture stripped away from them. Upon arriving at these schools, children had their hair forcibly cut and weren't permitted to wear of their traditional clothing. One of the best-known of these institutions was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the flagship native boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918.

- There are 11 federally recognized American Indian tribes in Wisconsin. Among them, there are three distinct linguistic groups: the Algonquian family, which includes Menominee, Ojibwe, Potawatomi and Mohican; the Siouan family, which includes Ho-Chunk; and the Iroquoian family, which includes Oneida.

- Religious suppression was a major factor in the disappearance of Native American languages. Native religions were actively suppressed through official U.S. policies, despite the enshrinement of religious freedom in the Bill of Rights. Anything related to Native American culture was seen as demonic, which led to peculiar place-naming conventions in Wisconsin and around the nation.

- In 2015, there were only 42 fluent Ojibwe speakers remaining in Wisconsin, with a few dozen more in Minnesota. In an effort to revive native languages, new immersion schools are being established up in Wisconsin, including. the Waadookodaading Ojibwe Language Institute in Hayward and Indian Community School in Milwaukee. (The work of the Waadookodaading school is featured in a video reportfrom The Ways, an educational project about Native American culture in the Great Lakes region produced by the Wisconsin Media Lab in collaboration with Wisconsin Public Television).

Key quotes

- Macaulay in response to the question, "Don't all languages die anyway?": "They rise up, then they fall down, it's a natural thing. Here's a quote from the late Ken Hale from 1992. He says, 'Language loss in the modern period is of a different character than before, in its extent and in its implications. It's part of a much larger process of loss of cultural and intellectual diversity in which politically dominant languages and cultures simply overwhelm indigenous local languages and cultures. The process is not unrelated to the simultaneous loss of diversity in the zoological and biological worlds.'"

- Valentine on the origin of the Devil's Lake placename in Sauk County and the perception of native religions as evil: "Why would this beautiful lake be called Devil's Lake? And I thought, well, there are many places around called Devil and such that if you do a bit of study, you'd discover that's the word for spirit in some Native American language. … The Ho-Chunk word is Teewakacak, which Tee means body of water and wakacak means spirit ... so Devil's Lake in Ho-Chunk is translated as 'spirits exist there.' And so we see this, but you could see just from the way that any spiritual aspect of Native American culture was interpreted as devilish and demonic and that sort of thing, and this is part of that suppression."

- Valentine on the importance of intergenerational relationships to learn language: "The Ho-Chunks especially have these daycare learning centers where elders work with the children and speak Ho-Chunk, and the children get the opportunity to learn the language. And they're really doing quite well with this as well. Again, you need a lot of fluent speakers who are mobile and able to get out and run around with children. But if you have those, these sorts of programs are very good."

- Valentine on the potential for longevity of the Ojibwe language: "Ojibwe is considered among the most likely Aboriginal languages of North America to survive for very long, mostly because of the large number of speakers in Canada."

- Macaulay on linguists' work to revive languages: "We can help communities document their languages. And so we record them, we make grammars of them, we work with the recordings, that kind of thing. We can help develop teaching materials. We can help work with people on methods, if we're trained in that ourselves. But we can't save languages. ... The ones who can do it are the language activists, that is members of the communities involved. They're the ones who can do it."

Editor's note: This item is updated to include additional quotations from Monica Macaulay.